Category:Brighton Royal Pavilion

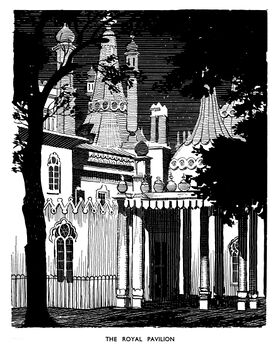

1935: "The Royal Pavilion", lineart by Arthur Watts [image info]

Brighton Pavilion (stained glass window at Brighton's Palace Pier) [image info]

Brighton Pavilion, from the Pavilion Gardens, 2011 [image info]

Brighton Pavilion, gallery, 2011 [image info]

"Entrance to Royal Pavilion, colourised postcard showing the entrance some time before the construction of the India Gate in 1921 [image info]

Brighton's Royal Pavilion was originally a farmhouse building across the road from The Steine, but was extensively and repeatedly redeveloped and extended to become the current structure.

The Marine Pavilion

Carlton House's designer, Henry Holland, was hired to extend and enlarge the farmhouse into something more suitable, and the original building became one of two neoclassical wings flanking a central domed rotunda, known as the Marine Pavilion.

More land was purchased around the building and used to build an impressive and ornate set of stables, which is now the Brighton Dome complex (and now incorporates the Brighton Dome and Brighton Museum and Art Gallery).

The Royal Pavilion

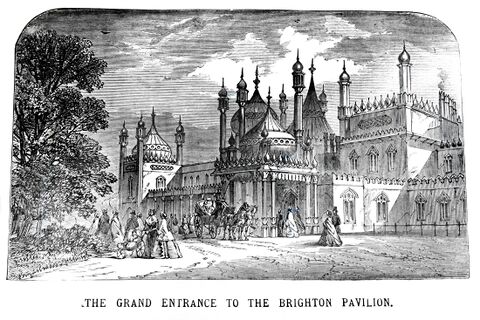

Perhaps spurred by comments that his horses lived in a finer palace then he did, George then hired John Nash (the architect of the Houses of Parliament) to revamp the Pavilion to become something rather more palatial, the result being an almost obscenely opulent-looking building with onion domes and an Indian-style exterior, and Chinese and Indian-themed interiors, with as much decoration as could be crammed into the available space.

How the Pavilion was Built

Persons who complain of the appearance of the structure to-day should spend a few minutes looking over the prints of what it was! For downright ugliness the Pavilion of 1788, or even that of 1818, can hardly have had an equal. Additional space was secured from time to time, and domes and pinnacles began to shoot up in all directions. Alteration succeeded alteration, addition followed addition, for something like a quarter of a century; until finally, in 1817, Nash, the architect who designed Buckingham Palace, Regent Street, and the Quadrant, took the building in hand, and left it, about 1819, externally much as it is to-day.

The earlier building and successive purchases of land cost nearly 70,000, and the town itself added much towards the grounds. What was spent on additions to the edifice, and in furnishing, no one knows. So carelessly and lavishly was the money laid out that the workmen, it is said, frequently drew sixteen days' wages a week. At a time when bread averaged from 11d. to 1s. per loaf, the Prince was sending agents to all parts of the world to select articles of furniture, regardless of cost, which, when sent home, were frequently relegated to the lumber room unused. No wonder that, later, Byron wrote in the fourteenth canto of Don Juan –

- " Shut up – no, not the King, but the Pavilion,

- Or else 'twill cost us all another million! "

Cobbett said, "A good idea of the Palace might be formed by placing the pointed half of a large turnip in the middle of a board, with four smaller ones at the corners"; while Sidney Smith caustically remarked, "One would think that St. Paul's Cathedral had gone to Brighton and pupped." Even loyal Sir Walter Scott, writing in 1826 to a friend who resided at Brighton, besought him to "set fire to the Chinese stables, and if it embrace the whole of the Pavilion it will rid me of a great eyesore."

It is only fair to say, however, that some authorities have spoken In terms of praise of the bizarre pile. Parry, in his Coast of Sussex (1833), says with some justice "It is true that the architectural taste of some may be averse to the adoption of the Chinese and Oriental style, yet by us who have 'some little turn that way' it was deemed on inspection to possess capabilities of beauty not inferior to the graceful Ionic, stately Corinthian, or elaborate, florid Gothic."

The Pavilion as a Royal Residence

No description of life in Brighton towards the close of the eighteenth century and the early years of the nineteenth can be complete without some allusion to the gay life led within the walls of the Pavilion when it was the residence of George, Prince of Wales. When, in the course of the numerous additions to the Pavilion, an adjoining tea-garden was taken in which contained a fine avenue of trees, a writer of the day remarked, with a near approach to the truth, that the colony of rooks which these contained was "the only respectable thing in the royal property.".

Gay, wild and rackety were the scenes within the Pavilion and in Brighton generally a century or more ago, when, to quote chronicles and scenery, Highways and byways in Sussex, the town " was the favourite resort of the First Gentleman in Europe"; when the Steine was a centre of fashion and folly; coaches dashed out of Castle Square every morning and into Castle Square every evening; Munden and Mrs Siddons were were to be seen at one or other of the theatres; Martha Gunn dipped ladies into the sea; Lord Frederick Beauclerk played long innings on the Level; and Mr. Barrymore took a pair of horses up Mrs. Fitzherbert's staircase and could not get them down again without the assistance of a posse of blacksmiths."

Sale to Brighton, 1850

George died in 1830, and when Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837 she didn't seem to approve of the Pavilion, which had a relatively small number of large rooms, whereas Victoria's family and entourage required a larger number of perhaps smaller rooms. The Pavilion was also too near the main road and Brighton was now starting to attract large numbers of day-trippers from London via the new railway line terminating at Brighton Station (1841). Victoria sold the Pavilion to Brighton in 1850, and had the loose fittings removed and taken away -- many of which subsequently migrated back to the Pavilion over the following years.

1883: Magnus Volk and electric lighting

... it was soon after this that he became interested in electric lighting. This led to his appointment as electrical engineer to the Corporation of Brighton, and in 1883 he lighted the Royal Pavilion estate electrically. This installation was then the largest of its kind in the country. A large chandelier in the Dome of the Pavilion was wired for 200 lamps, which had carbon filaments, and the 200 gas fittings in it were retained for possible use in emergency. This made Mr. Volk’s work more difficult, for his insulating materials had to be capable of withstanding the heat of the gas flames.

— , -, , The Career of Magnus Volk (1851-1937), , Meccano Magazine, , 1937

World War One

The Pavilion was then used as a military hospital for Indian soldiers during World War One, leading to the donation of the India Gate to the town in 1921 by grateful supporters back in India (including the Maharajah of Patiala).

1933 description:

MOST prominent and distinctive among the public buildings of Brighton is that Oriental structure, rich in cupolas and minarets, the laughing-stock of the witty and the admired of the many, that fantastic edifice which grew up, as we have already noted, at the bidding of, the fourth of the Georges, and rejoices in the name of —

The Royal Pavilion

Admission.—The principal suite of rooms may be viewed daily (Sundays excepted) from 10 a.m., to 1 p.m. on payment of 6d. (children, half-price). From May to October also on Monday afternoons from 2–5 at same charge. Ratepayers are admitted free on the first Monday in each month.

After having been partly dismantled, on the disuse of the building as a royal residence, the Pavilion was in 1850 acquired by the Brighton Commissioners as town property for the sum of £50,000. Bearing in mind the enormous sums that had been spent on the place, it cannot be said that Brighton made a bad bargain. The Pavilion has since been used for public purposes. The alterations and improvements were completed in 1864; and some of the superb chandeliers and other decorations, which had been removed previous to the sale, were restored by Queen Victoria, in answer to a request of the townspeople.

In 1898 Her Majesty also restored many of the original decorations of the Pavilion, which had been stored at Kensington Palace. In 1912 articles forming part of the famous Oriental "properties" of the Pavilion were found in a store-room at Buckingham Palace and were sent by Queen Mary to Brighton. They included glass ornaments used in the decoration Of chandeliers, patterns of mouldings of fantastic shape, and samples of wall-paper in keeping with the Chinese Gallery. Eight beautiful candelabra with tulip-shaped globes which belonged to the Pavilion and were removed to Windsor Castle were presented to the town by H.M. the King in 1920, and are now to be seen in their original positions in the Banqueting Room.

From November, 1914, until January, 1916, the Pavilion and the Dome were utilized as a hospital for wounded Indian soldiers; and later, until the summer of 1920, as a hospital for limbless men wounded in the War.

The grounds are entered by two gates. The dignified South Gateway – in such striking contrast to the florid buildings beyond – is not part of the original Pavilion. It was "the gift of India in commemoration of her sons who, stricken in the Great War, were tended in the Pavilion. Dedicated to the use of the inhabitants of Brighton by his Highness the Maharaja of Patiali on October 20, 1921." The gateway follows a sixteenth-century Gujerat design. The North Gate, which was the principal entrance at the time of the royal occupation, was built by King William IV in 1832.

The Pavilion has a stone front 200 feet long, and nearly in the centre is a dome, in the Oriental style, 130 feet high. It is a curious fact that no two rooms are alike.

The rooms are generally viewed in the following order, but consequent upon the opening of the King's Apartments on the ground floor and various rooms on the first floor the direction of visitors may be changed from time to time.

- We enter the show part of the Pavilion by a Vestibule, 26 feet either way, and having a tented roof.

- Having obtained admission tickets, we pass to the right into the Red Drawing-Room, its ceiling supported by wooden pillars carved to represent bamboo and its walls covered with specially designed paper. Note how the dragon of the wall-paper has been reproduced in the graining of the doors. It is said that a young labourer, amusing himself by copying on a door panel one of the dragons of the paper, was surprised by the Prince Regent, who so admired the work that he instructed him to carry out all the graining in like manner.

- Hence by a long corridor to the Great Kitchen, notable among other things for the palm-tree leaves which appear to sprout from the iron roof-pillars. The modern electric ovens beside the great open stove provide interesting comparisons. In the adjoining vegetable kitchen the covers of the coppers with the initials P.R. (Prince Regent) are worthy of attention.

- From the Kitchen to the Banqueting-Room. This apartment, 60 feet long by 42 feet wide, with a height under the dome of 45 feet, is fitted in the Chinese style, the walls being hung with canvas, which is panelled with a series of fifteen pictures of Chinese domestic life. A magnificent chandelier (weight 1 ton), now fitted with electric lights, hangs in the centre.

- The South Drawing-Room is a low, pleasant room overlooking the lawns and the Steine. It, also, is richly decorated.

- Beyond this is the beautiful Saloon or Rotunda, under the principal dome, which forms the centre of what is known as the "Grand Suite of Rooms." The greater part of the decoration is original. The paper on the walls, it is interesting to note, was made in 1921 from the original blocks.

- We next reach the North Drawing-Room – ceiling upheld by pillars around which serpents coil and which have capitals shaped like umbrellas from the ribs of which hang bells. These pillars are among the most bizarre of the many extraordinary decorations of the Pavilion.

- The Music Room, the ground plan of which is similar to that of the Banqueting-Room, is another lavishly decorated chamber – fearful dragons and glittering chandeliers combining to make a strange setting for the organ, presented to Brighton by Queen Victoria in 1848 and brought here from the old Royal Chapel of the Pavilion.

- From the Music Room opens the Chinese Gallery, low-roofed and gloomy during the daytime, but brilliantly illuminated by night by countless Chinese lanterns and with decorations in Chinese style – the inevitable dragon being well represented.

Most of the grand balls for which Brighton is famous are held in the Pavilion rooms, its spacious corridor and the ornate decorations rendering it very suitable for such a purpose.

The upper rooms of the Pavilion, low-roofed and unattractive, are reached by staircases with bamboo-shaped balustrades. They are nearly all appropriated to a splendid series of drawings and pictures illustrative of ancient and modern Brighton, collected by the late Mr. Crawford J. Pocock and the late Mr. Furner, and secured by public subscription. Additions are constantly being made. This collection and the contents of other rooms on the same floor constitute a supplementary Museum.

— , -, , A Pictorial and Descriptive Guide to Brighton and Hove, 10th Edition, , Ward, Locke & Co Ltd., , 1933

External links

- Royal Pavilion, homepage (brighton-hove-rpml.org.uk)

- Brighton Pavilion (historicengland.org.uk)

- History of the Indian Gate, by Bert Williams (mybrightonandhove.org.uk)

- Unveiling of the Indian Gate — 26 October 1921 (rpmcollections.wordpress.com)

music:

- The Pavillion: a favourite Rondo for the Piano Forte, Composed by Matthias Holst (imslp.org)

- The Brighton Railroad Quadrilles, and Pavilion Waltz, by Frederick Wright (invaluable.co.uk)

Pages in category ‘Brighton Royal Pavilion’

The following 3 pages are in this category, out of 3 total.

Media in category ‘Brighton Royal Pavilion’

The following 16 files are in this category, out of 16 total.

- Brighton By Night, by HG Gawthorn (BrightonHbk 1935).jpg 2,200 × 1,502; 2.44 MB

- Brighton Map (VisitBrighton 2011).jpg 1,417 × 3,000; 4.04 MB

- Brighton Pavilion (stained glass at Brighton Palace Pier).jpg 1,600 × 1,600; 288 KB

- Brighton Pavilion 043, 2011.jpg 1,650 × 2,200; 1.29 MB

- Brighton Pavilion 048, 2011.jpg 2,200 × 1,650; 1.4 MB

- Brighton Pavilion Grand Entrance, engraving (NGB 1885).jpg 2,200 × 1,467; 878 KB

- Brighton Pavilion in 1788 (NGB 1885).jpg 2,200 × 1,462; 635 KB

- Brighton Pavilion, Ted Bayley, detail.jpg 1,600 × 1,200; 1,010 KB

- Brighton Science Festival, poster (BSF 2016).jpg 605 × 857; 146 KB

- Heritage Learning Brighton and Hove.jpg 142 × 120; 9 KB

- Old Steine (BHAD10ed 1933).jpg 3,000 × 1,893; 3.29 MB

- Pavilion Estate, 1939 map (BrightonHbk 1939).jpg 1,371 × 1,372; 929 KB

- Royal Pavilion, lineart, Arthur Watts (BrightonHbk 1935).jpg 1,776 × 2,200; 1.8 MB

- The Prince of Wales' Pavilion at Brighthelmstone, after Charles Middleton 1788.jpg 2,200 × 1,539; 509 KB

- The West Front of the Pavilion, from a drawing by Pugin 1888.jpg 2,200 × 1,480; 431 KB